Thanks to COVID-19 many of us have become ‘experts’ at participating and hosting online meetings via platforms such as Zoom, Teams or Skype etc. Interacting with people in the virtual world is now considered the “new norm” while face-to-face meetings have lost their undisputed importance.

This year, board directors have been challenged to make vital strategic decisions without the luxury of face-to-face meetings. While most boards are still considering the right balance between holding meetings in the physical and virtual world, many boards have noted the benefits of online board meetings. These include:

- reduced travel and increased attendance due to convenience of access

- opportunities for shorter but more regular meetings including committee meetings

- opportunities to recruit a wider range of directors due to decreased geographical constraints

- the ability for board directors to conveniently access and participate in online professional development.

Board directors are deciding how best to harness the benefits of the online space to access professional development and facilitate better engagement in board meetings. The following are some useful tips for keeping a virtual meeting on point and productive:

- Choose the right platform: While different platforms offer various security controls, as with most technologies, what matters is how they are implemented and enforced. Boards and company secretaries must work with IT to ensure appropriate settings are in place to protect the confidentiality of board documents and decisions.

- The Chair has a vital role: The online housekeeping protocols should be clearly articulated by the Chair at the start of each meeting.

- Meeting minutes continue to be important: This is particularly the case where the board are making decisions about the financial sustainability of an organisation or where there are challenging decisions that may attract increased stakeholder or regulator scrutiny.

- Consider a blended approach: While many boards are eager to get back to face-to-face interactions, there is scope to adopt a blended approach. Boards may find that the work of committees can be achieved online while board meetings are conducted face-to-face.

- Bring in the experts: Consider bringing in subject matter experts for 10-15-minute time slots. Potential guests may be easier to secure as travel and the associated costs will not be a barrier to their participation. Similarly, for boards that have been considering accessing professional secretarial services (either through a named outsourced company secretary or a support company secretary), these services may become more accessible through an online format.

What are the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on school boards’ decisions regarding financial reserves?

The Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC) has been providing advice to not-for-profit (NFP) organisations in this area, hosting webinars such as “Managing charity money in the wake of COVID-19” and podcasts such as “Charities dealing with financial difficulties” while Chartered Accountants ANZ have been encouraging NFPs that it is now “more vital than ever to have cash in reserve [as] those charities with cash reserves are often best equipped to survive”.

What are reserves and why are they important?

Reserves are funds that have been ‘set aside’ or accumulated over time to provide an NFP with financial stability and to help it manage risk. These reserves assist in responding to unexpected events and the associated costs.

Good governance practises stipulate that a charity’s Board should consider an appropriate level of reserves for its circumstances and a strategy for accumulating and using its reserves in a way that is consistent with its purpose to ensure its financial stability and sustainability.

For an NFP, ‘reserves’ usually refers to funds commonly called ‘operating reserves’ or unrestricted funds available for discretionary use. Schools may consider descriptors such as “retained earnings’’, ‘’financial year surplus’’, “working capital”, “savings for future building projects” or ‘’available cash” (at the lowest point of the year) as their reserves. If reserves are backed by cash and not restricted to particular uses, they can provide some comfort during a downturn.

What is an appropriate level of reserves?

The ACNC suggests there is no single level of reserves which will be appropriate for all. Each charity should assess its situation, decide on the level of reserves taking into account risks such as current and future liabilities, potential changes in income, external trends and events, etc. In the UK, charities are required to discuss and document their decisions about reserves at least once per year.

Responding to questions at a recent governance event, Elizabeth Jameson, Deputy Chair of the board of directors of RACQ explained that a robust risk appetite discussion should occur before determining the level of reserves a board is comfortable to accept.

Regardless of the level, the decision to either accumulate or use-up reserves without a clear explanation or justification may affect the public’s perception of a charity, which leads to the need for a reserves policy.

What is a reserves policy?

According to the ACNC:

“A charity should develop and implement a policy that governs their charity’s use of reserves. A policy can provide guidance and rules for the responsible persons which ensure that the charity’s reserves are being used for their proper purposes…. [and] in ensuring their charity remains solvent and financially stable”.

Important considerations for a reserves policy should include answers to these questions:

- What is the appropriate level of reserves?

- How is the level determined?

- Who is the decision-making authority?

- What will be the strategy for building reserves and how will it be communicated?

- What will be the criteria for spending?

- How will the process be reviewed?

Reviewing a charity’s level of and purpose for reserves should be a regular part of a Board’s financial governance practices.

Is your board adding real value to the school?

Being a board member of an independent school is a rewarding and worthwhile undertaking, but it requires a significant time commitment. To exercise one’s powers and discharge one’s duties with a reasonable degree of care and diligence, directors spend considerable time and effort in the execution of their role. With the many hours they spend each year on reading board papers, studying financial statements and keeping informed about the school’s strategic operating environment, board members would expect that the investment of their time will bear fruit and place the school in a better position.

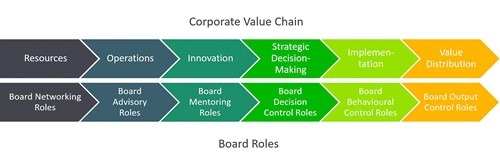

Boards wishing to reflect on the value they contribute to their organisation should consider the following model. Figure 1: Board roles and the corporate value chain (Huse et al., 2005)

Figure 1: Board roles and the corporate value chain (Huse et al., 2005)

This simple model aligns each phase of an organisation’s value chain with a board role.

- Schools rely on tangible and intangible resources to enable the delivery of a high-quality education service to students and families. The goodwill and support derived from strong connections with various stakeholders (customers, financiers, local community, government, etc.) can help a school to flourish. By initiating and maintaining critical relationships as part of the networking role, directors can provide an influential link between their organisation and its external environment, adding value in ways no other stakeholder can.

- The core of a school’s operations lies in the excellent delivery of an education service, supported by ancillary functions that provide the foundations for success. Directors bring unique personal and intangible skills and competencies to the board that can add value to the operational decisions of the school’s Head. Care must be taken not to confound this advisory role with becoming a de-facto operational decision-maker.

- Continually developing new services, processes and markets through innovation ensure the sustainability of the organisation. Innovation requires a reflective outlook on future opportunities, courage, and a culture of trust. A strong relationship between the Head and Chair (or other directors) fulfilling a mentoring role can set the scene for this culture and improve the creative process of identifying problems and developing solutions.

- Boards engage in decision-making crucial to the long-term development of the school. They also ratify and control decisions made by the school’s Head. They add value to the school by engaging in their decision-control role. Directors bring diversity of perspective and deep insight into the complex cognitive tasks required to make responsible decisions that appropriately consider risk appetite, values alignment and long and short-term perspectives.

- Good strategic decisions are only as good as their implementation. Boards engaging in their behavioural control role evaluate the outcomes of past decisions, monitor the performance of the school’s Head, and track the school’s performance by previously identified success indicators. With this task requiring significant time and effort, boards add most value by identifying and prioritising those activities, risks, external environments and cultural elements that are most influential in creating value for the school.

- Lastly, schools create value by making good decisions about the investment of surplus funds. This value distribution is controlled by boards enacting their output control role. Directors add value to this task when they responsibly consider and balance internal and external stakeholders’ interests before concluding and moving forward with what is in the best interest of the organisation.

Boards wishing to be of most value to their school are encouraged to reflect on this model and identify areas of strength and future development.

Reference: Huse, M., Gabrielsson, J., & Minichilli, A. (2007). Knowledge and accountability: Outside directors’ contribution in the corporate value chain. Board members and management consulting: Redefining boundaries: Special volume in research in management consulting series.

Independent schools currently operate within an expansive and complex regulatory framework that provides extensive safeguards to protect children from institutionalised abuse. Schools have existing reporting obligations under numerous Acts and their subordinate Regulations.

In August, the Criminal Code Act 1899 was amended to include two new offences that will increase personal liability in relation to responding to allegations of child sexual abuse:

- Section 229BB Failure to protect child from child sexual offence

- Section 229BC Failure to report belief of child sexual offence committed in relation to a child

These changes are in response to recommendations made by the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in their Criminal Justice Report in 2017 and carry a maximum penalty of five (5) and three (3) years imprisonment respectively.

Failure to protect explained

This provision requires individuals with power or responsibility (an accountable person), who know there is a significant risk that another adult will commit a child sex offence in relation to a child, to reduce or remove the risk. Wilfully or negligently failing to do so attracts a maximum penalty of five years imprisonment.

It is reasonable to assume a school board director would be considered an accountable person and has a responsibility to remove or reduce the risk other adults pose to children.

Failure to report explained

The provision mandates that where an adult gains information that causes the adult to believe on reasonable grounds, or ought reasonably to cause the adult to believe, that a child sexual offence is being committed or has been committed against a child by another adult, and at the relevant time the child is or was under 16 years of age or a person with an impairment of the mind, the adult must, unless they have a reasonable excuse, disclose the information to a police officer as soon as reasonably practicable after the belief is, or ought reasonably to have been, formed. If the adult fails to do so they commit a misdemeanour that attracts a maximum penalty of three years imprisonment.

Any adult who follows the reporting obligations as outlined in the school’s compliant Child Protection policy and procedure will have fulfilled the new reporting obligation under the Criminal Code.

These provisions will commence on a date set by proclamation to allow the necessary implementation activities, such as training, to occur. ISQ will advise all schools once the date has been set.

Board Chair Interview

Brad Beasley

Chairman of The Board of Trustees, The Rockhampton Grammar School

Trustee since 2001 | Chairman since 2009

What excites you about your school?

A number of things excite me about The Rockhampton Grammar School: The quality of people at the school; the educational opportunities offered to students; the wide co-curricular program; and the variety of properties available to students to support their education: an Early Learning Centre, rugby fields, a rowing facility, a beach-front outdoor education facility and a working cattle property.

What prompted you to become a Trustee?

I'm a past student of RGS and developed an interest in governance through my legal career. Having a not-for-profit commitment allows me to give back to the community. Since my passion is for education, whether it be at my work with emerging lawyers or through the education system, becoming a Trustee at RGS was the obvious choice.

How would you describe an effective board?

An effective board is well-educated in governance and ensures that it doesn't accept management's verbal or written reports without appropriate challenge. Effective boards have a skills matrix that ensures members have the right skill sets, and their composition is adequately diverse. In addition, effective boards are made up of compassionate people, particularly when they are dealing with significant amounts of students, parents and teachers whose perspectives should be taken into consideration.

What is your advice for new school board members?

Before their appointment, potential members should be very clear about their motivations to join the board, as some reasons, such as having children at the school, can lead to conflicts of interest. Secondly, they should get a full understanding of what their role entails. Thirdly, they should complete relevant governance courses. Finally, they should do their due diligence on the school to ensure they are thoroughly aware of the issues they will be dealing with both in the near term and medium term.

How can boards make good decisions despite an ambiguous and uncertain future?

Most organisations haven’t had a playbook on how to deal with a disruption like the pandemic. During uncertain times, we aim at making good decisions by working hard, forming a cohesive unit and meeting with Management regularly to work through the issues. In long-term matters involving uncertainty, we look to gain an early and deep understanding of the concerns and their implications, and avoid making decisions on the run. We treat these issues as much as possible as business-as-usual cases in which we are having to make strategic decisions.

Recent